Exploring the Forest Through Our Senses

Our meditation walk in Nosara’s green zone. Image: Veronica Monge

An abridged audio recording of this walk is available at the end of the post.

“They say that sounds give us the story of the forest,” says Jeff.

We all close our eyes and open our ears. We’re standing at the threshold of a path leading into the Costa Rican jungle, listening attentively to the six directions around us. We don’t have to wait long for the forest to speak to us.

The throaty hoots of an animal pierce our meditative silence. We avoid the urge to open our eyes and look. It’s quite possibly Alouatta palliata, the Mantled Howler Monkey, which is common to Nosara. The males use an enlarged hollow bone near their vocal chords to amplify their howls, which are signals to other groups of monkeys to stay away from his group’s territory.

A local howler monkey. Image: Jonathan Nimerfroh

“We’re exploring the sense of moving through a soundscape,” says Jeff as the hoots fill the air, “and, apparently, the territory of a bunch of monkeys. What stories are emerging in the sounds you’re hearing? What stories are getting triggered in the mind’s eye?”

We’re on the Green Zone Meditation Walk, offered every Tuesday by the Healing Centre. Though we’re walking through one of many deep, green thickets that span Nosara’s Green Zone – an area near its shoreline that is protected from development – it’s not your typical nature walk. It’s less about learning about bird calls and pizote tracks than it is about meditating your way through nature.

Our guide here is Jeff Warren, who is offering meditation workshops this month as Harmony Writer-in-Residence. A self-professed nature lover whose first book was a guide to the Canadian wilderness of Algonquin Park (and here I must betray my journalistic objectivity – I know all this because he is also my fiancé!), Jeff asks us to approach both the mind and the forest as curious explorers. He offers a quote from American 19th-century naturalist John Burroughs on the nature of paying attention:

“Can you bring all your faculties to the front, like a house with many faces at the doors and windows; or do you live retired within yourself, shut up within your own meditations?”

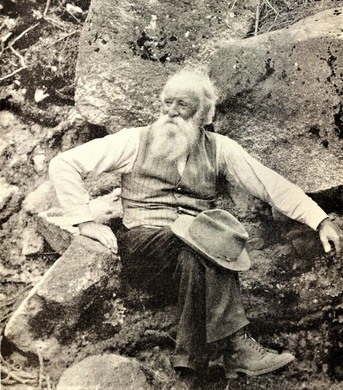

Naturalist John Burroughs

As we’re digesting this, we’re asked to play a challenging game. We must split into pairs, and one of us must close her eyes; the other person guides their hands towards various textures.

“Your partner is your eyes and you are the hands,” says Jeff. “You really want to train your attention and see if you can create an image of what you’re feeling.”

I close my eyes, and my partner – the lovely Monica Ramos, Creative Director of Harmony’s Healing Centre – tells me to walk forward and crouch down. I trust her, nervously. My fingers brush rough, woody textures; a plump fan of leaves. I’m handed a pom-pom shape that exudes a faint perfume. My attention is rarely so awake, so primed to focus on every sensation.

“Careful with this one,” says my partner, gradually guiding my hand toward something. It’s spiky and sharp. It could cut me, but I investigate it further, brushing my fingers over its stiff points. Next, she hands me something cottony soft and fragile. How could a natural environment encourage two diametric opposites to evolve and coexist in the same few square metres?

Getting to know the pochote tree. Image: Sarah Barmark

I open my eyes and see my spiky friend: Pachira quinata, the pochote tree, a common fixture in the Nosara jungle and all along the country’s west coast – but a sharp rebuke to sentimental North American treehuggers. Covered in grey spines up to an inch long that wouldn’t look out of place in the movie Hellraiser, the tree is outfitted to keep animals off. Yet one varietal of this forbidding tree is prized and cultivated here for its wood, excellent for furniture.

Yet I was in for a surprise: the fragrant, fresh, springy pom-pom I’d so enjoyed holding was none other than the flower of the exact same pochote. With a spray of white stamens exploding from a fleshy pod, it attracts birds and insects (and human noses) to the small store of honeyed nectar deep in its base in exchange for spreading its pollen in its flowering months, March and April. The ground beneath us was littered with dried versions of the flower, which had turned from white to burnt red.

The pochote flower

Meanwhile, the cottony softness I’d touched had been an open seed pod, which could have been produced by any one of the trees around us. The fan of long leaves had been a giant fern. So many textures!

Our final meditative cue was also our most mystical.

“We’re going to go into what’s called the participatory mode of perception,” says Jeff. He invites us to broaden our gaze, to make it passive, allowing sights and other sensations to come to us rather than us reaching outside ourselves for them. Then, he asks us to try to experience nature not as something “in an art gallery,” but as something we’re in relationship with right now.

“As you’re touching the ground, can you feel that the ground is touching you back?” “That your own feet are being touched by the earth, just as the air is sampling your skin? That slight breeze isn’t just you feeling the breeze, but the breeze is also feeling – tasting – you.”

This hints at a subtle but significant transformation. We were never here to explore nature, to observe it and peer at it. It’s not about us and it. We are a part of nature and it is a part of us. This truism is something many naturalists, farmers, conservationists and other nature-lovers know without needing to meditate – but it is certainly a realization that meditation (rather paradoxically for a process that is ostensibly about going inward) can apparently speed up.

Jeff quotes our friend, the deep ecologist David Abram (only a truly hopeless nerd quotes books on a nature walk):

“The human body is not an enclosed or static object, but an open, unfinished entity utterly entwined with the soils, waters, and winds that move through it – a wild creature whose life is contingent upon the multiple other lives that surround it, and the shifting flows that surge through it.”

And so we stagger onward through the Green Zone, a short walk in space, but long in perspective.

Editor’s note: You can listen to the audio of the walk on the player below, or download the mp3 file to your computer by right clicking HERE and then choosing “download linked file” from the menu. While it’s impossible to portray the full experience of this walk solely through audio, it’s our hope that it gives a sense of the beautiful natural sounds of our local forest, and that Jeff’s meditation cues can be inspiration for mindfulness that you can listen to and practice wherever you are.

Sarah Barmak is a journalist and author. Her first book, Closer: Notes from the Orgasmic Frontier of Female Sexuality, was published last year by Coach House Books to much acclaim.

Jeff Warren is a writer and meditation instructor. He is the author of The Head Trip, a travel guide to sleeping, dreaming and meditation that many critics enjoyed, although his mother thought it was too long.