Michael Gaillard

The Harmony Hotel’s first Artist in Residence talks with the Harmony Blog about his work past and present.

Artist Michael Gaillard is grappling with too many names. For over a decade now, he has produced photographs of Nantucket landscapes as “Michael Gaillard,” while making a separate, more conceptually driven body of work under his New York moniker, “Michael Stuart.” But his dual identity—inspired by the fact that certain more traditional kinds of art-making can sometimes find a lukewarm reception in Chelsea galleries—soon became hard to maintain, according to Gaillard: At openings, people would ask, “What’s your name?” And he’d respond. “Gaillard, well, Gaillard, but really Stuart.” Explains Gaillard, “I’d tell the whole story. And it became untenable. It never felt right.” Gaillard notes he is proud of both bodies of work, and says of the Nantucket photography, “It allows me to make art without having to have another job.” (As a photography professor at Columbia University, though, he does enjoy continuing to teach: “It complements my art,” he says.)

Even when Michael’s creating not just photographs but also sculptures and video, it seems that much of his work is arguably concerned with (as he articulately puts it) “the paradoxical and untenable relationship that exists between the image contained within a photograph and the material presence of the photograph.” He says, “The inherent approach to a photograph—and one of the things that relegates it to a position of weakness in relation to other fine arts in the eyes of many artists—is the acceptance that it’s merely a window into a perceived experience. Rather than being filtered through some sort of artistic consciousness; manipulated by some sort of artistic gesture.”

Here, he reflects on several artworks he’s made over the past decade:

Origin, 2010

This is documentation of a sculptural installation featured in my thesis exhibition for the MFA program at Columbia University. As you can see, all of the weather vanes are almost identical except for the one that served as the template for the rest. The original is a classic piece of American folk art that was common throughout the 19th century and into the 20th. This particular piece was always on the mantle in my great-aunt’s house on Nantucket and was given to me upon her passing. Although it bears great personal symbolic significance to me, it also carries symbolic weight in a broader sense, both in terms of the way in which a weather vane functions, as well as the symbolism of the angel Gabriel and its relevance to the theme of this piece. The copies of the original are all cut from the same piece of tree and arranged according to the 16 points on the compass. The original is signifying a WNW wind, the direction the wind was blowing at the moment of my birth.

I see this piece as a manifestation of the human inclination to assign finite origins to infinitely complex systems. Physically, the vanes all point inward, seeming to fly toward this singular point, signaling a collision, and yet, symbolically, functionally, the vanes signify dispersion from that point. All winds emerge from that imagined center.

To take this further, I am interested in this fixing of a fluid and dynamic substance. As we do with wind, so too, we do with our lives. And photography both literally and metaphorically, contributes to this aim. Much like a photograph exists as a fixed point in the passage of time from past to present and on. Much has been said about the death implied in a photograph:

“For the photograph’s immobility is somehow the result of a perverse confusion between two concepts: the Real and the Live: by attesting that the object has been real, the photograph surreptitiously induces belief that it is alive, because of that delusion which makes us attribute to Reality an absolute superior, somehow eternal value; but by shifting this reality to the past (‘this-has-been’), the photograph suggests that it is already dead.”

— Roland Barthes, Camera Lucida: Reflections on Photography

Contingence, 2010

I have wrestled with the medium of photography for some time now, and the complications with it heightened greatly when I entered into an interdisciplinary MFA program in which I found many discourses that existed outside and often even in opposition to the discourse common among photographers’ photographers. The deadness to which Barthes refers above may have contributed to some of this opposition, as those in that camp often seemed to be uninterested in a medium that merely pointed to another time, another place without occupying the same space they did. I think for some time I started to align myself with those who saw photography as lacking the agency of other mediums, and therefore lacking complexity.

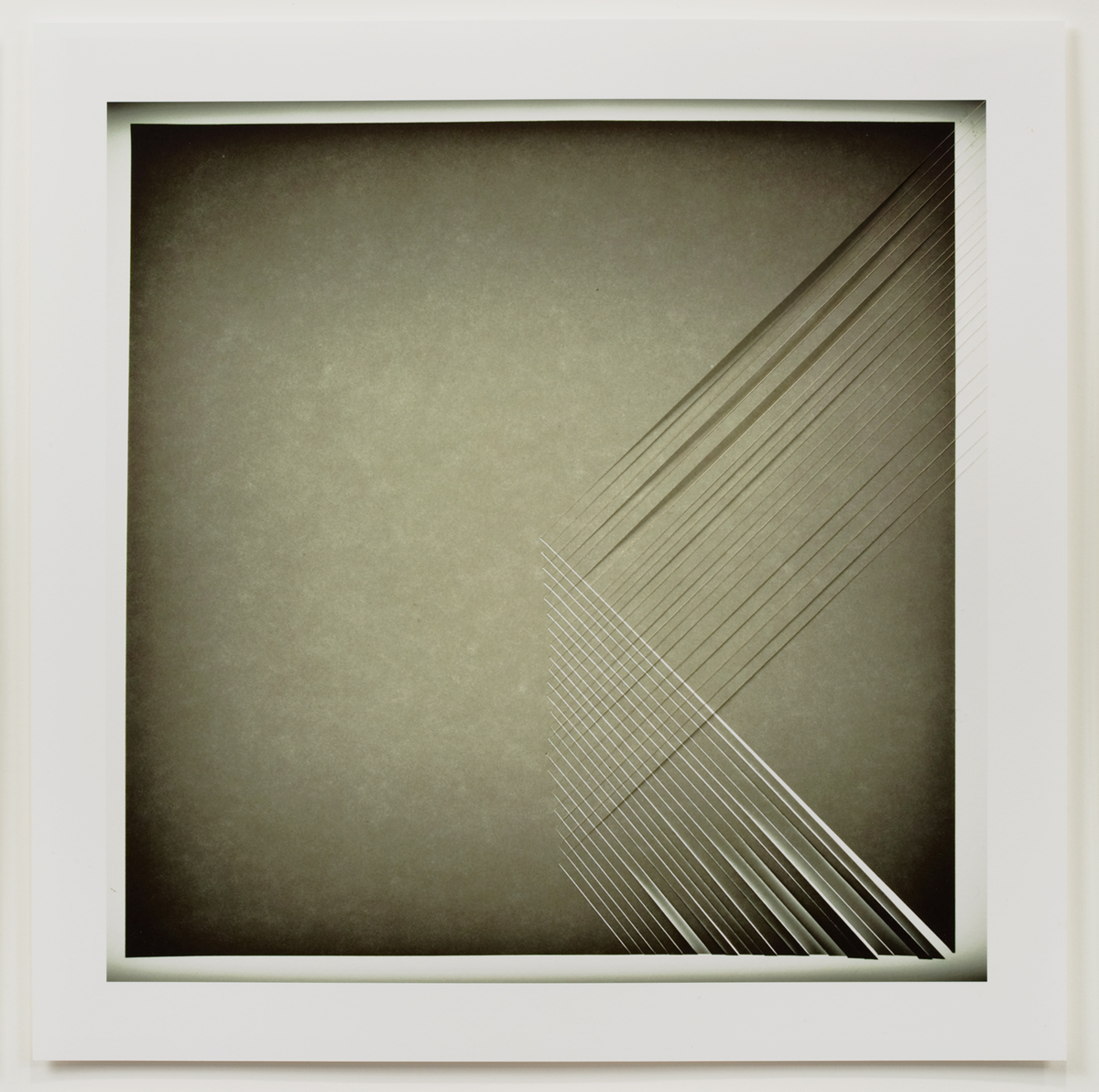

This piece, “Contingence,” was born out of a realization toward the end of my time in graduate school when I started to consider ways in which I might address the inextricable relationship between the surface of the photograph, the very material of the photograph, and the image contained within its frame. So much art today engages surface and reflects on the intricacies of gesture and the complexities of artistic agency, and yet so much photography remains victim to the limits prescribed by the medium’s original, more mechanical, ambitions. “Contingence” is a series of photographs, 27 in all, depicting the progression of a simple series of gestures. Starting with a square blank sheet of paper, I used a blade to cut an incision from the center of the square to the bottom right corner. I then photographed that piece of paper on a light table, printed the photograph, and made an incision from origin of the first incision (now rendered in the photograph, in light) to the top right corner of the photograph. I proceeded to continue this system until the cuts on the original paper reached the bottom of the square. This resulted in 27 cuts, by chance, and thus the 27 panels in the series.

I see this piece as a reflection on the inextricable link between the surface of the photograph (which I link to the context in which the photograph is presented and seen) and the content contained within the photograph. The two bound, overlapping, and interdependent. The real cut becomes contingent to the photographed cut, and yet the photographed cut is more visible than the real. The point at which the two incisions meet is an impossible hinge between the real and the represented, the present and the memory of a present passed.

Screen, 2011

|

|

This is a two-channel video (that you can see here) of wind passing through a screen and a curtain—one at night, one during the day. I came to this subject spontaneously one afternoon as I returned to my bedroom in a Nantucket B&B. The piece’s full meaning is rendered in its installation, which involves projecting the day on one side of a screen hanging in the middle of a room, and the night on the other side of that same screen. The idea is related to the way I see time and surface in “Contingence,” but manifested differently. Here I see the image of the wind as this random and ever-changing clear substance, only recorded in the movement of what it touches, passing through an infinitesimal screen that is the screen, both in the video, as well as symbolically in the room. I see the screen as symbolically linked to the surface of the photograph and philosophically bound to the present moment—our image of time passing going in one direction while our projections of our visions go in the other.

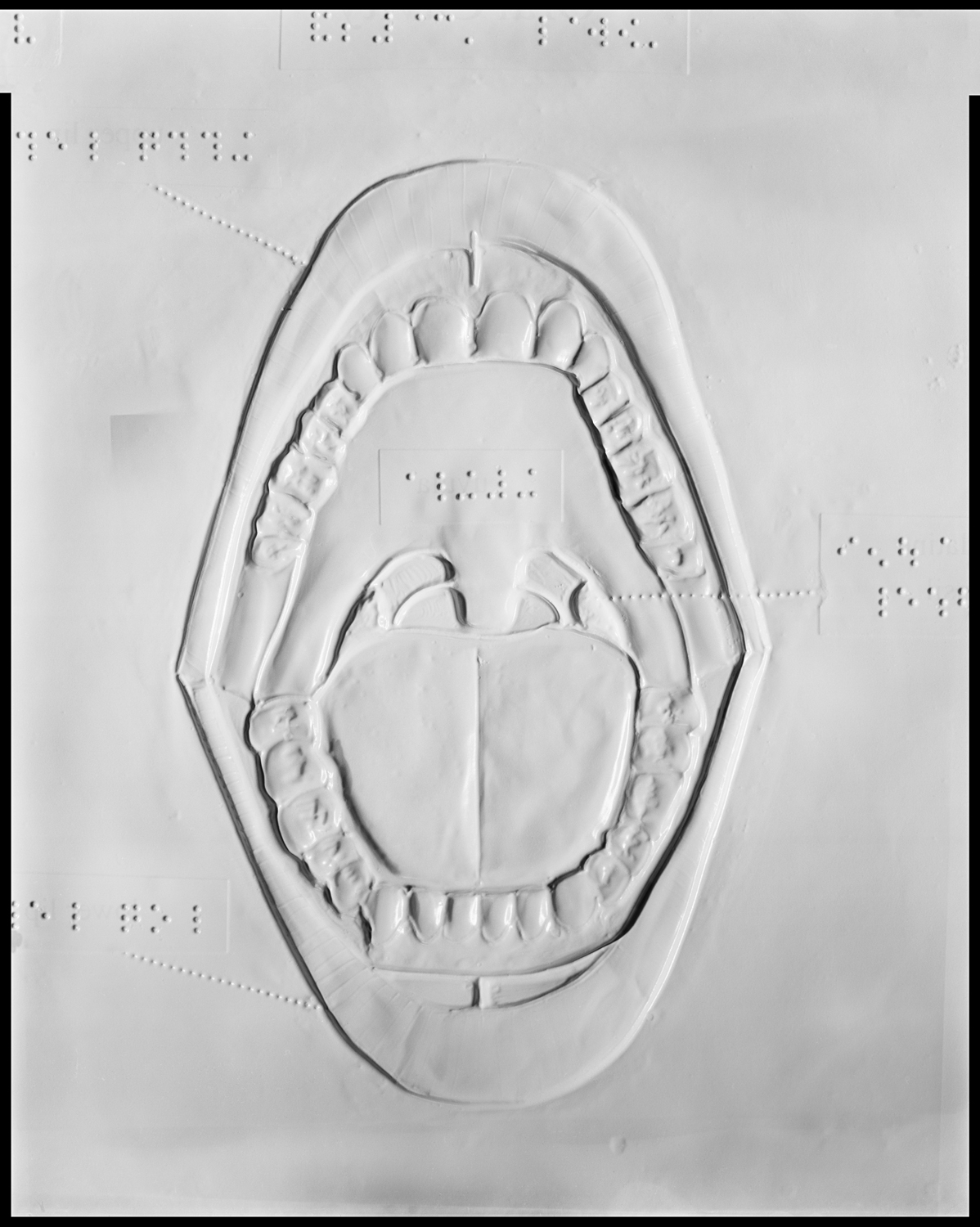

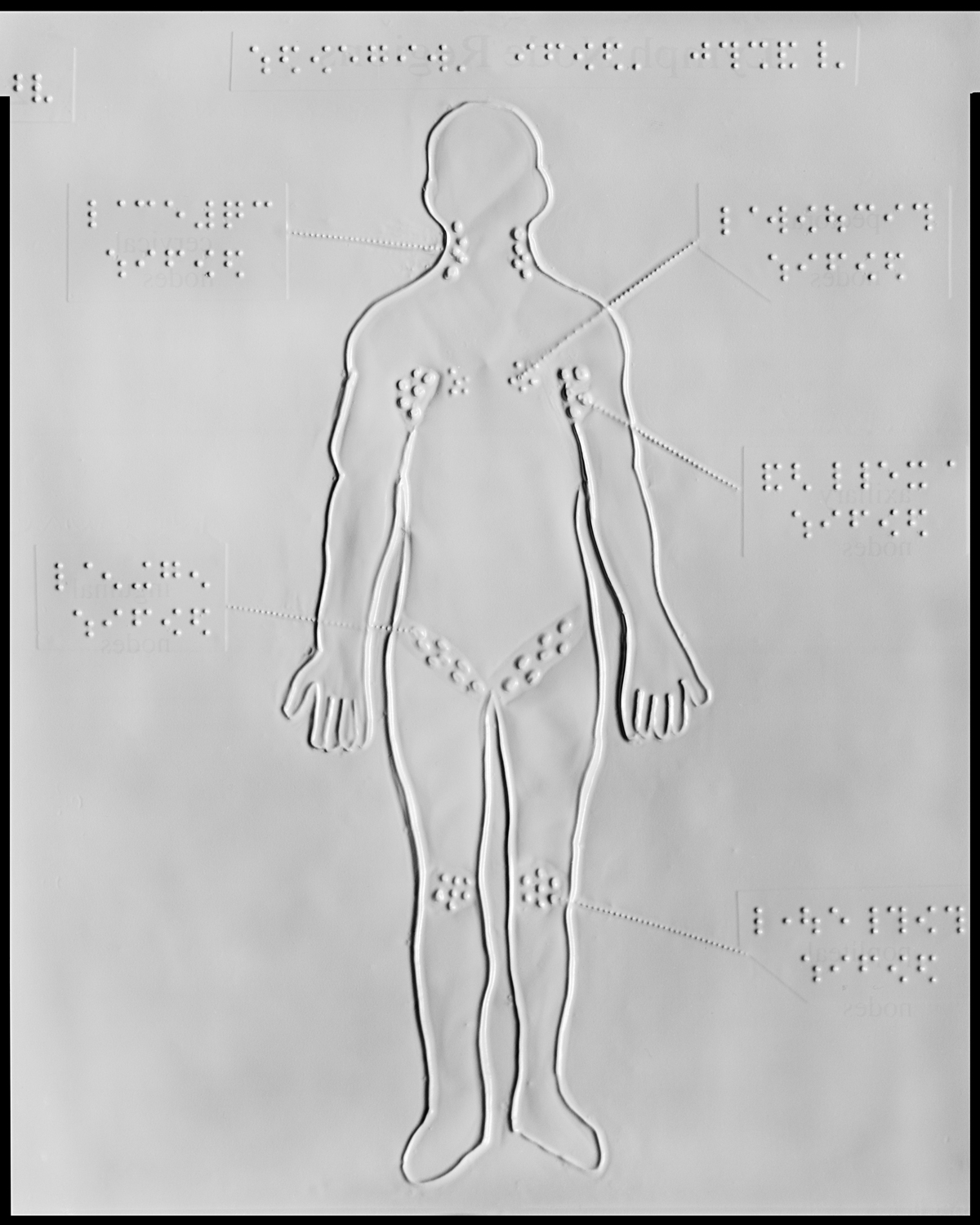

Mouth and Lymphatic System, 2009

|

|

These are two images from a series of photographs taken of pages in an anatomy book for the blind. If you look on my website, you can see the rest under “Braille Studies.” I thought it might be interesting to photograph documents intended for the blind, ultimately erasing the content for the documents’ original audience. It calls to attention the act of reading as a feeling, as a sense—something that exists within us all.

I am very much interested in the limitations of the photograph, and by extension, limitations in perception and comprehension. I find the most interesting spaces to be those where language and description fail to encapsulate that which is being depicted. I find photography fascinating because of its ability to describe so much detail and yet it ultimately fails to say much of anything beyond what the audience can bring to it. A picture may be worth a thousand words, but what words the picture conjures are different in each moment and to each of its viewers. If photographs really did succeed at describing their subjects, then captions would never be necessary. I feel as though sight is the most deceptive sense, and as such, photography the most deceptive medium.

Jetties, 2008

I don’t really believe I am photographing the landscape when I am photographing Nantucket. I feel as though I am photographing the air and the light, a smell, a particular wind and the salt on its wings. The landscape serves as the stage or backdrop that makes the rendering of that sensation possible. I know it sounds pretty crazy, but those who know Nantucket well know exactly what I am talking about. Actually, I think everyone has a place like that—a place that goes far beyond an objective appreciation of beauty. It reminds us of something timeless, something great, something ineffable that passes over and through us that has existed long before and will continue to exist long beyond.

Polpis, 2010

I used to feel as though I needed to mark a division between the Nantucket work and my more conceptual, often studio-based work because the former seemed so remote from the latter in terms of intention, execution, and character. But now I feel differently. The thing that joins the two practices is necessity and sincerity. I believe in the necessity of both if I am to continue to grow, both as an artist and a person. Both the bodies of work need to be made, and both come from a sincere desire to make something meaningful and lasting that grows with me and us as time marches incessantly on.

Gaillard will be in Nosara in February as an artist-in-residence at the Harmony Hotel. Look for him there! Or see more of his work here and here.